Related:

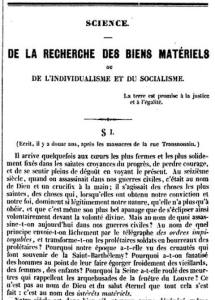

Pierre Leroux’s essay on individualism and socialism was part of (at least) three different larger projects. In the first volume of the Oeuvres de Pierre Leroux (1850) it appears as part of an “Appendice aux trois discours,” along with a number of other early essays. (This is the version translated here.) In the Revue Social (1845) it appears as part of a 6-part essay, “De la recherche des biens matériels ou de l’Individualisme et du Socialisme,” where the 1850 text makes up the first of two sections in the first part. (All but the first and sixth installments became part of the book Malthus et les économistes, ou, Y aura-t-il toujours des pauvres?) And if we go back to its first appearance in Revue encyclopedique (1834), it appears (along with another 1000 words of text, appended in translation at the bottom of this page) as part of an article, “Cours d’économie politique fait à l’Athénée de Marseille par M. Jules Leroux,” that is apparently a commentary on and introduction to the lectures given by his brother (and partially reproduced in the Revue.) Digging back into earlier issues of the Revue encyclopédique, we find another essay, “Du progrès législatif,” which discusses the dangers of individualisme, but without references yet to socialisme. In that essay, the contrast is between individualisme and association, with the latter clearly a more unambiguous good:

From the most general point of view, the social question does not today specifically concern one class of society more than another; but it embraces them all. It is not only a question of the proletarians: it is a question of humanity, of all its faculties, of all its heritage; it is a question of the coordination of all human knowledge; it is necessary to attach all the progress of science to legislation; and from this labor must emerge a new order, which realizes the higher ideas of justice and equality that the human mind has conceived as a consequence of its initiations. But from the particular point of view of politics, the entire question is summed up and laid out in the advent and elevation of the proletariat.

The Third estate and the Proletarians: to these two terms there today correspond two entirely opposite doctrines. One is individualism which, under the pretext of leaving each free in the use of their faculties, results only in the reign of a petty aristocracy. The other is the doctrine of association, the doctrine of the French Revolution, the doctrine of organized equality.

Equality in and through association, that is where all the avenues of the past steer us, where all the efforts of the present tend, where all the sparks cast by the future lead.

There is obviously a good deal here to digest and several threads to untangle before we can fully understand the essay that has come to be known as “Individualism and Socialism” in its original context(s). I’ll be adding and linking new translations providing those contexts as time allows.

- “Du progrès legislative,” Revue Encyclopédique 59 no. 167 (November, 1832): 259–276.

- “Cours d’économie politique fait à l’Athénée de Marseille par M. Jules Leroux,” Revue Encyclopédique 61 (October, 1833): 94–117.

- “De la recherche des biens matériels, ou de l’Individualisme et du socialisme, 1er article,” Revue Social 1 no. 2 (November, 1845): 18–25.

Revue encyclopédique

- Du progrès législatif

- Cours d’économie politique fait à l’Athénée de Marseille par M. Jules Leroux

De la recherche des biens matériels ou de l’Individualisme et du Socialisme (Revue social)

- 1er article. [de l’Individualisme et du Socialisme]

- 2ème article : Les Juifs rois de l’époque.

- 3ème article : L’Economie politique et l’évangile. A propos d’une conférence du R.P. Lacordaire.

- 4ème article : L’Humanité et le Capital

- 5ème article : Y aura-t-il toujours des pauvres?

- 6ème article : Relations du Travail et du Capital

Appendice aux trois discours.

- De l’Union Européenne.

- Étude sur Napoléon.

- De la Poésie de Style.

- Plus de Libéralisme impuissant

- De la Nécessité d’une Représentation spéciale pour les Prolétaires.

- De l’Individualisme et du Socialisme.

- De l’Economie Politique Anglaise.

- La France sous Louis-Philippe.

Malthus et les économistes, ou, Y aura-t-il toujours des pauvres?

- Les Juifs rois de l’époque.

- L’Economie politique et l’évangile.

- L’Humanité et le Capital

- Y aura-t-il toujours des pauvres?

INDIVIDUALISM AND SOCIALISM.

By Pierre Leroux

(1834.—After the massacres on the Rue Transnonain.)

I

At times, even the most resolute hearts, those most firmly fixed on the sacred belief of progress, come to lose courage and to feel full of disgust at the present. In the 16th century, when one murdered in our civil wars, it was in the name of God and with a crucifix in the hand; it was a question of the most sacred things, of things which, when once they have procured our conviction and our faith so legitimately dominate our nature that it has nothing to do but obey, and even its most beautiful appanage disappears thus voluntarily before the divine will. In the name of what principle does one today send off, by telegraph, pitiless orders, and transform proletarian soldiers into the executioners of their own class? Why has our epoch seen cruelties which recall St. Bartholemew? Why have men been fanaticized to the point of making them coldly slaughter the elderly, women, and children? Why has the Seine rolled with murders which recalls the arquebuscades of window of the Louvre? It is not in the name of God and eternal salvation that it is done. It is in the name of material interests.

Our century is, it seems, quite vile, and we have degenerated even from the crimes of our fathers. To kill in the manner of Charles IX or Torquemada, in the name of faith, in the name of the Church, because one believes that God desires it, because one has a fanatic spirit, exalted by the fear of hell and the hope of paradise, this is still to have in one’s crime some grandeur and some generosity. But to be afraid, and by dint of cowardice, to become cruel; to be full of solicitude for material goods that after all death will carry away from you, and to become ferocious from avarice; to have no belief in eternal things, no certainty of the difference between the just and the unjust, and, in absolute doubt, to cling to one’s lucre with an intensity rivaling the most heated fanaticism, and to gain from these petty sentiments energy sufficient to equal in a day the bloodiest days of our religious wars, this is what we have seen and what was never seen before.

What indeed is the principle conquerors of the day have put forward? In the name of what idea have they declared in advance that they would bequeath to posterity the example of a decimated generation? And what is the drive that they have made play to gain that victory? It is neither an idea nor a principle. Everyone knows it. It is not a secret for anyone that the great words order and justice today only conceal the interests of the shops. Business is bad, and it is the innovators, it is said, that stand in its way: war then against the innovators. The workers of Lyon associate in order in order to maintain the rate of their salary: war, then, and war to the death, against the works of Lyon. Always, at the bottom of all of this, are the interests of the shops. In the days of mourning, so often renewed these past three years, the people have been told: here is a holy, just, legitimate idea, by virtue of which you can kill men. It is not so. But on the eve of each riot one cries to the people: Tomorrow your profit will be diminished, your daily receipts will be less, your material satisfaction will be compromised And that has been enough, and we have seen the shopkeepers in hunting gear, armed with double-barreled rifles, to aim more accurately and to kill two instead of one, go merrily to hunt among the blocks. Is there in such a spectacle something to trouble our convictions, and to make us doubt progress; and, since we are condemned to civil war, must we long for civil war as our ancestors knew it, atrocious but religious, deliberately bathing itself in blood, but with eyes lifted towards heaven? In that fury which, according to Bonald, often sent the innocent and the guilty, pell-mell, before their eternal judge, because it deliberately sacrificed the earth to heaven, we must regret the presence of the monster egoism, which has nothing of God, which, like the harpies, has only the hunger of its belly!

In past times, there was the nobility, and there was the clergy: the nobility had a maxim not to occupy itself with lucre; the clergy condemned usury, and regarded as inferior the condition of merchants. There were certainly men then who knew no other morality than their own selfish interests, and no other reason for things than their calculating tables; but they had not set the tone and did not lay down the law for society; they were not the arbiters and legislators. If they wished to rise that far, and to apply their narrow rules to things in general, they were ridiculous, and the poets availed themselves gladly of the comedy and satire, where they came immediately below the lackeys. Today these men enjoy the leading role; the very same society has no other law, no other basis nor end, than the satisfaction of their affairs. Humanity has not lived and suffered to bring about the reign of the merchants. Jesus Christ once chased the merchants from the temple: there are today no other temples than those of the merchants. The palace of the Bourse has replaced Notre Dame; and we know no other blazon than the double-entry cash-books. One passes from a boutique to the Chamber of Deputies, and one carries in public affairs the spirit of the sales counter. Our ancestors made crusades: we, we wisely calculate that that cost the bourgeois the conquest of Algiers, and we will gladly abandon to the English the civilization of Africa, if it gets a little expensive. The zeal of St. Vincent de Paul appears stupid to the general councils: is it not a revolting iniquity to charge the rich for the upkeep of the children that the poor abandon! Since money is everything, and the order of the bourgeois has replaced nobles and priests, is it astonishing that the blood of one bourgeois does not appear to us overpaid by the blood of a thousand proletarians, and is it not completely natural put the interests of the shops on a level with the blood of men? I kill, says the merchant, because I have been disturbed in my affairs: it is a compensation that is due to me for the loss that I feel. By this account, Shylock was right to want to carve human flesh: had it not been purchased?

Seen in this way, our century could not be more base. Material interests, there is the great watchword of society; and many innovators have themselves ignominiously eliminated from their mottoes the moral and intellectual amelioration of the people, in order to preserve only their material betterment.

Is it the case that we will sink more and more in this way, and that the shame may be reserved for France that, having proclaimed to the world the brotherhood of man, it transforms itself into what Napoleon has called with scorn a nation of shopkeepers, supported in their avaricious domination by the facile courage of an army of stipendiaries?

We know of noble hearts, of high intelligences, which fear it. We fall back, they cry, into Roman corruption and into the moral of the barbarians: of what use to us are eighteen hundred years of Christianity, and the conquests of science and industry?

It is to these generous, but discouraged, hearts, that I intend to respond, in occupying myself with political economy, that is, with the material aspect of society. I will attempt first, today, to expose for them the sense of that greediness which shows itself, it is true, among all the classes, but which, among men of power, struts about so hideously, sheltered by the bayonets of our soldiers; and in the subsequent articles, I will attempt to demonstrate that if the social question presents itself in our time primarily as a question of material wealth, it is because the human sciences are very close to finding the solution.

II

We say, then, that that exclusive preoccupation with material things which reigns today, that species of domination by egoism and the material, is nothing which must surprise or discourage us. In all periods of renewal, the renovation of material things has been one of the forms of progress. Every great human evolution is at once material, moral, and intellectual, and cannot not have these three aspects. To imagine that Christianity, for example, or any other great religious revolution, has related solely in its principles what is called heaven and not to the things of the earth, to morals or ideas, and not to interests, would be an absurd illusion, conceivable only by those who know the foundation of Christianity only by the sermons of their priest, but impossible for whoever has glanced at history. Christianity has been able to say: “My kingdom is not of this world; but by doing so it has powerfully altered the material constitution of that world, out of which it would direct the contemplation of men, towards a mysterious future. In the presence of pagan society, founded on individualism and slavery, Christianity posed the Essene way of life and the community of good; and from that new form given to material life resulted the dissolution of pagan society, the overthrow of the Roman world, and, as a result, the uselessness of slavery and its abolition. In the Protestant era, wasn’t something analogous seen? Didn’t we then see Christianity, attempting to regenerate itself, struggle for earthly goods against the Church, holder of those goods? Material interests played a huge role in the Reformation. The Reformation began in the 14th century with a violent and general struggle in Europe against the religious orders. It was the religious orders, that society in community without women and children, which, consequently, was only an exception and allowed to subsist outside of it the great, the true society, had however amassed such an enormous portion of the property, that the other society could no longer live; it was necessary then to recapture from it the land and all the instruments of labor that it had monopolized. Thus in the greatest and most exalted epochs, one finds again the question of material life.

But today it is evident that that which was only a secondary characteristic of previous revolutions must become a principle characteristic. Indeed, what do we want and where do we tend, on the faith of all the prophecies? The one who truly follows Jesus Christ with an intelligent heart, and not as a copyist without intelligence, does not say so absolutely that the kingdom of God is not on earth.(1) He understands that the epoch of realization approaches more and more. The stoicism of Zeno and the Christian stoicism are with reason relegated to their place in history. These two doctrines, or rather that doctrine, is today without social value. That was the debut of an immense career that Humanity has had to follow up to us. But where we have arrived today, heaven and earth begin to be without connection and without relation; and, instead of returning us toward the point of departure, towards the detachment and the retreat into ourselves of Jesus Christ and of Zeno, we must, by the efforts of our thought and the energy of our soul, transform the earth in such a way that the justice of heaven reigns there, in order one day to find that heaven so promised to our wishes.

The idea has been elaborated and preached by Christianity to all men, of a better world than the one which existed, of a world of equality and fraternity, of a world without despots and without slaves. Christianity has raised up humanity by hope; it has mystically announced its destiny; it has connected to the memories of its cradle, to its primitive and natural liberty, to its traditions of a past golden age, of Eden and of the native parade, the firm and assured sentiment of a golden age to come, of a paradise on earth, where the good will reign after the defeat of evil, and where man, redeemed by the divine word, will again find happiness, and enjoy an unalterable felicity. And, at that prophecy, one sees human society divide itself in two: the religious society, indifferent to the present enjoyments of the earth, or only using them in order to practice complete equality, community, individual non-property, as symbol of what will one day be the justice of heaven; and the secular society, which continua, under the teachings of the other and under its spiritual government, human life such as one had known it previously. Now, by Protestantism and by Philosophy, the religious society has been destroyed, and there is today only one society. The consequence, I repeat, isn’t it clear and evident? Isn’t it obvious that the principles of the world prophesied and awaited for so many centuries by the religious society must be realized more and more in the only society that exists today? Or else Humanity would have declined and degenerated, Christianity would have been an imposture and a chimera, and everything, in the eighteen hundred years which have passed, would only be comedy and deception. The earth, then, is promised to justice and equality.

Christianity, Reform, Philosophy, follow one another like the acts of a drama which approaches its dénouement. Those who consider history on in a casual manner, and page by page, must often find contradictory and incoherent that which is harmonic and continuous. Seeing the Reformation succeed Catholicism, and Philosophy succeed the Reformation, how many people are shocked, and see there only negation, discord and uncertainty! It is because they do not understand the series and the generation of things. So for them, there is death, there is nothingness, in these alternations and these contrasts, while for us, it is life. Their eyes offended by deep darkness, there where a dazzling light shines in ours. For what contradiction is there between the successive acts of a single drama, between the connected and coherent phases of a single evolution? It is only necessary to rise up enough to grasp and contemplate all at once the spirit of evolution in its entirety; and for anyone who is enlightened, that effort is not difficult. That alleged anarchy of Catholic Christianity, of the Reformation, and of Philosophy, succeeding and combating each other by turns, is not a very obscure enigma, the sense of which would be difficult to discover. We see Christianity first raise above the world its mystical paradise, like the seed which begins to form in the air, and which then waits until the winds spill it on the ground. The Reformation came after, which spread the promise to all of society, and, by laying waste to all pious retreats where the spiritual life had been concentrated, made only one single people, that it raises to spiritual dignity. Then in its turn comes Philosophy, which further extends this level, and which finally, explaining the prophecy, interprets the reign of God on earth as perfectibility. Christianity, Protestantism, and Philosophy, have thus driven towards the same end, and accomplished by various phases one single work. We are the last wave that the hand of God has pushed up to here on the shore of time: but the consequence of all the previous progress has not escaped us, and that obvious competition of three great phases which divided the centuries which preceded us is the token of all the progress to come.

Thus the earth, I repeat, is promised to justice and equality. Material goods are in themselves neither good nor bad. All the metaphysicians have come to see in matter and in body the limit of forces, the place where finite intelligences meet and are mutually revealed. Bodies and matter are the field of our faculties, the necessary means of their exercise, the milieu in which they are manifested. That there is in us, and in each of us, a force, created or uncreated, which animates us, constitutes us, and survives the destruction of what we call our body, is for me an obvious truth; but it is always the case that the force, either in this life, or in our previous or future lives, exerts itself only through the intermediary of bodies, precisely because it has limits and it is finite. The Christians, in the good days of Christianity, and even during the history of Christianity, have never understood the activity of the soul at the end of time without the resurrection of the body; and it has always been of the belief that man is, according to the expression of Bossuet, a soul and a body united together, an intelligence destined to live in a body. The Manicheans alone, exaggerating and distorting spiritualism, have entered into the error of regarding matter as absolute evil; and, by that same error, they fell inevitably under the empire of evil, in wanting to escape it.

Thus, whether we appeal to religious traditions and to the previous life of Humanity, or whether we consult only modern reason and the general agreement of the men of our era; far from condemning the use of material goods, we must see that none of our most noble faculties can be exercised without the mediation of these goods.

From this is follows that, all having been called to the spiritual life and to the dignity of men by the words of the philosophers, all must soar, and that legitimately, towards the conquest of material goods.

It is his dignity, it is his capacity as a man, it is his liberty, it is his independence, that the proletarian demands, when he aspires to possess material goods; for he knows that without these goods he is only an inferior, and that engaged, as he is, in the labors of the body, he partakes more of the condition of the domestic animals than that of man.

It is the same sentiment which pushes those who these goods to preserve them. Of course, we are not the apologists of the wealthy classes, we are with the people, and we will always be for the poor against the privileges of the wealthy; but we know that, whatever the softness and the egoism which reign in these classes, men absolutely corrupted and bad are the exception. In the present struggle of the proletariat against the bourgeoisie, that is of those who do not possess the instruments of labor against those who possess them, the bourgeoisie represents even, at first glance, more obviously than the proletarians, the sentiment of individuality and liberty. The wealthy possess that liberty, and they defend it, while the proletarians are so unhappy and so deprived of it, that a tyrant who promised to free them by enriching them could perhaps, in their ignorance, make of them for some time his slaves.

We find then good and legitimate that tendency of those who possess liberty and individuality to preserve it; but couldn’t they find equally just and legitimate the demands of those who do not possess them, and want to?

There is, we say, the sense and the justification of that struggle for material goods, which seems, at first glance, the dominant character of our era, and which would dishonor it if one did not consider what it reveals, and if one had not studied the religious necessity scope of it. That demand for material goods is not at all immoral: very far from that, it is the result and the consequence of all the previous progress of Humanity.

Certainly, the philosophers who only hold as good, in human nature, the side of devotion, must find our era deplorable in all regards. For pure devotion, where will they find it? In their hearts, doubtless, and in the hearts of a certain number of generous men who take up the cause of the people. But society, viewed en masse, and in its truest aspect, did not meet their expectations. Devotion, as they sanctify it, they will find it neither in the wealthy classes nor among the poor, neither in the bourgeoisie nor among the proletarians. The first want to preserve, and the others to acquire: where is the devotion?

Pure devotion, however noble it may be, is only an individual passion, or, if you wish, a particular virtue of human nature, but is not human nature in its entirety. A man who would, in every aspect of his life, act on the basis of devotion, would be an insane being; and a society of men for whom the single rule would be self-sacrifice, and who would regard every individual act as evil, would be an absurd society. Thus, every theory which would found itself on devotion as on the most general formula of society, and who would deduce then from that expression some laws and institutions that is would have a hope of applying with force to society, would be false and dangerous.

But, on the contrary, a general principle which represents and expresses complete human nature, is the principle of liberty and individuality.

Our fathers put on their flag: Liberty, Equality, Fraternity. Let their motto still be our own. They did not conclude from I know not what social system to the individual; they did not say: Society must inevitably be organized in such and such a manner, and we are going to chain the citizen to that organization. They said: Society owes satisfaction to the individuality of all, it is the means of liberty for all.

The sentiment of liberty, as the Eighteenth Century and the French Revolution have felt and promulgated them, is an immense progress over the devotion or devoutness of Christianity, and it would be a regression to desire today to despotically organize society according to the particular views that one may have, instead of founding it on the principles of individuality and liberty.

Proclaim the system that will best satisfy the individuality and liberty of all, and do not fear that the devotion of the people would be lacking for you; for such an aim will be felt by all, and it is the only one which could excite devotion today. But devotion for its own sake would be as absurd a theory as the art for art’s sake of certain litterateurs.

III.

One can paint a portrait, equally hideous and true, of man in the state of absolute individuality and of man in the state of absolute obedience. The principle of authority, even disguised under the good name of devotion, is no better than the principle of egoism, hiding itself under the good name of liberty.

We also reject with all the forces of our soul Catholicism under all its disguises and in all its forms, whether it attaches itself again, by I know not what puerile hopes, to the old debris which are at Rome with the ruins of so many centuries, or whether, by who knows what jesuitism [escobarderie], it pretends to incarnate itself anew in Robespierre, become the legitimate successor of Gregory VII and the inquisition. And at the same time we regard as a scourge, no less fatal than papistry, the present form of individualism, the individualism of English political economy, which, in the name of liberty, makes men rapacious wolves among themselves, and reduces society to atoms, leaving moreover everything to arrange itself at random, as Epicurus said the world is arranged. For us, the papal theories of every sort and the individualist theories of every species are equally false. They could be fatal, if they were not equally powerless; but papistry, dead for some many centuries, will not prevail against the entire modern era, and the modern era, as we have demonstrated elsewhere, carries in itself the promise and the seed of a society, and is not the destruction and negation of every society.

Liberty and Society are the two equal poles of social science. Do not say that society is only the result, the ensemble, the aggregation of individuals; for we will arrive at what we have today, a dreadful pell-mell with poverty for the greatest number. Theoretically you would have still worse; for, society no longer existing, the individuality of each has no limits, and the reason of each has no rule: you would arrive at moral skepticism, at general, absolute doubt, and in politics at the exploitation of the good by the malicious, and of the people by some rascals and some tyrants.

But do not say any more that society is everything and that the individual is nothing, or that society comes before the individuals, or that the citizens are not anything but some devoted subjects of society, functionaries of society who must find, for good or ill, their satisfaction in all that which contributes to the social aim; do not make of society a sort of large animal of which we would be the molecules, the parts, or the members, of which some would be the head, the others the stomach, the others the feet, the hands, the nails or the hair. Instead of society being the result of a free and spontaneous life for all those who compose it, will not want the life of each man to be a function of the social life that you would have imagined: for you will arrive by that path only at brutalization and despotism; you would arrest, you would immobilize the human spirit, all while pretending to lead it.

Do not attempt to bring back to us the government of the Church; for it is not in vain that the human spirit for six centuries against that government, and has abolished it.

Do not attempt to apply to our era that which was suitable in previous eras, the principle of authority and sacrifice; for the authority and self-sacrifice of the previous life of Humanity aimed precisely to arrive at individuality, at personality, at liberty. That was good in the past, but it was good precisely on the condition that it would lead to a goal, and that once Humanity arrived at that goal, it would cease to be, and that this government of the world would make place for another.

We are even today the prey of these two exclusive systems of individualism and socialism, pushed back as we are from liberty by that which claims to make it reign, and from association by that which preaches it.

Some have posited the principle that every government must one day disappear, and have concluded from it that every government must from now on be confined to the narrowest dimensions: they have made of government a simple gendarme charged with responding to the complaints of the citizens. Moreover, they have declared the law atheist in any case, and have limited it to ruling the disagreements of individuals with regard to material things and the distribution of goods according to the present constitution of property and inheritance. Property thus formed has become the basis of that which remains of society among men. Each, retired on his bit of land, became absolute and independent sovereign; and all social action is reduced to making each remain master of the plot of land that inheritance, labor, chance, or crime had obtained for him: Each by himself, each for himself. Sadly, the result of such a renunciation of all social providence is that each does not have his bit of land, and that the portion of some tends always to increase, and that of the others to diminish; the well-demonstrated result is the absurd and shameful slavery of twenty-five million men over thirty.

Others, on the contrary, seeing evil, have wanted to cure it by an entirely different process. Government, that imperceptible dwarf in the first system, becomes in this one a giant hydra which embraces in its coils the entire society. The individual, on the contrary, absolute sovereign and without control in the first, is no longer anything by a humble and submissive subject: he was once independent, he could think and live according to the inspirations of nature; he became a functionary, and only a functionary; he is regimented, he has an official doctrine to believe, and the inquisition at its door. Man is no longer a free and spontaneous being, he is an instrument who obeys in spite of himself, or who, fascinated, responds mechanically to the social action, as the shadow follows the body.

While the partisans of individualism rejoice or console themselves on the ruins of society, refugees that they are in their egoism, the partisans of socialism, (2) marching bravely to what they call an organic era, strive to discover how they will bury every liberty, all spontaneity under what they call organization.

The first, entirely in the present and without future, have come as well to have no tradition, no past. For them the previous life of Humanity is only a dream without consequence. The others, carrying in the study of the past their ideas of the future, have taken up with pride the line of the catholic orthodoxy of the Middle Ages, and they have said anathema to all of the modern era, to Protestantism and to Philosophy.

Ask the partisans of individualism what they think of the equality of men: certainly, they will keep themselves from denying it, but it is for them a chimera without importance; they have no means of realizing it. Their system, on the contrary, has for consequence only the most unspeakable inequality. From this point their liberty is a lie, for it is only the smallest number who enjoy it; and society becomes, as a result of inequality, a den of rascals and dupes, a sewer of vice, suffering, immorality and crime.

Ask the partisans of absolute socialism how they reconcile the liberty of men with authority, and what they make, for example, of the liberty to think and to write: they will respond to you that society is a grand being of which nothing can disturb the functions.

We are thus between Charybdis and Scylla, between the hypothesis of a government concentrating in itself all the lights and all human morality, and that of a government deprived by its very mandate of all light and all morality; between an infallible pope on ones side and and a vile gendarme on the other.

The first call liberty their individualism, they will gladly call it a fraternity: the others call their despotism a family. Preserve us from a fraternity so little charitable, and let us avoid a family so intrusive.

Never, it is necessary to avow it, have the very bases of society been more controversial. If one speaks of equality today, if one shows the misery and absurdity of the present mercantilism, let one blacken a society where the disassociated men are not only strangers among themselves, but necessarily rivals and enemies, and all those who have in their heart the love of men, the love of the people, all those who are children of Christianity, Philosophy and the Revolution, become inflamed and approve. But let the partisans of absolute socialism come to outline their tyrannical theories, let them speak of organizing us in regiments of scientists and regiments of industrials, let them go as far as declaring against the liberty of thought, at that same instant you feel yourself repulsed, your enthusiasm freeze, your feelings of individuality and liberty rebel, you start back sadly to the present from dread of that new papacy, weighty and absorbent, which will transform Humanity into a machine, where the true living natures, the individuals, will no longer be anything by a useful matter, instead of being themselves the arbiters of their destiny.

Thus one remains in perplexity and uncertainty, equally attracted and repulsed by two opposite attractors. Yes, the sympathies of our era are equally lively, equally energetic, whether it is a question of liberty or equality, of individuality or association. The faith in society is complete, but the faith in individuality individuality is equally complete. From this results an equal impulse towards these two desired ends and an equal increase of the exclusive exaggeration of one or the other, an equal horror of either individualism or of socialism.

That disposition, moreover, is not new; it already existed in the Revolution; the most progressive men felt it. Take the Declaration of Rights of Robespierre: you will find formulated there the most energetic and absolute manner the principle of society, with a view to the equality of all; but, two lines higher, you will find equally formulated in the most energetic and absolute manner the principle of the individuality of each. And nothing which would unite, which harmonizes these two principles, placed thus both on the altar; nothing which reconciles these two equally infinite and limitless rights, these two adversaries which threaten, these two absolute and sovereign powers which both [together] rise to heaven and which each [separately] overrun the whole earth. These two principles once named, you cannot prevent yourself from recognizing them, for you sense their legitimacy in your heart; but you sense at the same time that, both born from justice, the will make a dreadful war. So Robespierre and the Convention were only able to proclaim them both, and as a result the Revolution has been the bloody theater of their struggle: the two pistols charged one against the other have fired.

We are still at the same point, with two pistols charged and pointed in opposite directions. Our soul is the prey of two powers that are equal and, in appearance, contrary. Our perplexity will only cease when social science will manage to harmonize these two principles, when our two tendencies will be satisfied. Then an immense contentment will take the place of that anguish.

IV.

In waiting for that desired moment, if one asks us for our profession of faith, we have just made it, and we are ready to repeat it; here it is: we are neither individualists nor socialists, taking these words in their absolute sense. We believe in individuality, in personality, in liberty; but we also believe in society.

Society is not the result of a contract. For the sole reason that men exist, and have relations between themselves, society exists. A man does not make an act or a thought which does not concern more or less the lot of other men. Thus, there is necessarily and divinely communion between men.

Yes, society is a body, but it is a mystical body, and we are not its members, but we live in it. Yes, each man is a fruit on the tree of Humanity; but the fruit, in order to be the product of the tree, is no less complete and perfect in itself; he contains in germ the tree which has engendered him; he becomes himself the tree, when the other will fall from old age under the shock of the winds, and it will be him who will bring new blood to nature. Thus each man reflects in his breast all of society; each man is in a certain manner the manifestation of his century, of his people and of his generation; each man is Humanity; each man is a sovereignty; each man is a law, for whom the law is made, and against which no law can prevail.

Because I live bodily in the atmosphere, and I cannot live an instant without breathing, am I a portion of the atmosphere? Because I cannot live in any way without being in relation and in communion with the external world, an I a portion of that world? No; I live with this world and in this world: that is all.

And just so, because I live in the society of men and by that society, am I a portion, a dependency of that society? No, I am a liberty destined to live in a society.

Absolute individuality has been the belief of the majority of the philosophers of the Nineteenth Century. It was an axiom in metaphysics, that there existed only individuals, and that all the alleged collective or universal beings, such as Society, Homeland, Humanity, etc., were only abstractions of our mind. These philosophers were in a grave error. They did not understand what is tangible by the senses; they did not comprehend the invisible. Because after a certain amount of time has passed, the mother is separate from the fruit that she carried in her womb, and because the mother and her child form then two distinct and separate beings, do you deny the relation which exists between them; do you deny what nature shows you even by the testimony of your senses, to know that that mother and that child are without one another beings that are incomplete, sick, and threatened with death, and that the mutual need, as well as the love, make from them one being composed of two? It is the same for Society and Humanity. Far from being independent of all society and all tradition, man takes his life in tradition and in society. He only lives because he as at one in a certain present and in a certain past. Each man, like each generation of men, draws his sap and his life from Humanity. But each man draws his life there by virtue of the faculties that he has in him, by virtue of his own spontaneity. Thus, he remains free, though associated. He is divinely united to Humanity; but Humanity, instead of absorbing him, is revealed in him.

If there are still in the world so many miserable and vicious men, of we are all affected by vice and misery, that reveals to us the ignorance and immorality which still afflicts Humanity. If Humanity was less ignorant and more moral, there would no longer be so many miserable and vicious beings in the world.

We are all responsible to one another. We are united by an invisible link, it is true, but that link is more clear and more evident to the intelligence than matter is to the eyes of the body.

From which it follows that mutual charity is a duty.

From which it follows that the intervention of man for man is a duty.

From which follows finally a condemnation of individualism.

But from that follows as well, and with an equal force, the condemnation of absolute socialism.

If God had desire that men should be parts of Humanity, he would have enchained them to one another in one great body, as the members of our body are connected to one another. To desire to enchain men thus, would have been as if, having recognized the invisible link that unites the mother and child, and which makes only one being of the two, you would desire to deny, because of that, their personality and enchain them to one another. You would return them by this to the previous state where they made strictly only one being; and, by reason of what they are now, you would constitute a state that is monstrous and as abnormal the state of absolute separation where you would have first desired to hold them. They are two, but they are united; there is relation and communion between them, but not identity. The one being who reunites them is God, who lives at once in the one and the other; and if he has separated them, it is in order that they should each have their individual life, even though they are connected to one another, and that under the relation that unites them they make only one single being. What is more, it is clear that the common life which unites them will be as much more energetic, as their individual lives are more grand. If the mother is happy, the child will be happy; and if the soul of the child is opened to enthusiasm and to virtue, the love of the mother will be will be exalted in it. Thus the social body will be made more happy and more powerful by the individuality of all its members, than if all men had been enchained to one another.

We arrive thus at that law, as evident and as certain as the laws of gravitation: “The perfection of society is the result of the liberty of each and all.”

At the end of the day, to adopt either individualism or socialism, is to not understand life. Life consists essentially in the divine and necessary relation of individual and free beings. Individualism does not comprehend life, for it denies that relation. Absolute socialism does not comprehend it better; for, by distorting that relation, it destroys it. To deny life or to destroy it, these are the alternatives of these two systems, of which one, consequently, is no better than the other.

(1) Jesus, in the Gospel, did not say, “My kingdom is not of this world; that was the bad translators who, by suppressing three words in one phrase of St. John, have made it say this. Jesus said literally, “My kingdom is not yet of these times.” And as his kingdom, as it is explained in the same passage, is the reign of justice and truth, and as it adds that this kingdom will come on the earth, it follows that, very far from have prophesied that the principles of equality will never be realized on earth, Jesus on the contrary prophesied their realization, their reign, their arrival.

(2) It is clear that, in all of this writing, it is necessary to understand by socialism, socialism as we define it in this work itself, which is as the exaggeration of the idea of association, or of society. For a number of years, we have been accustomed to call socialists all the thinkers who who occupy themselves with social reforms, all those who critique and reprove individualism, all those who speak, in different terms, of social providence, and of the solidarity which units together not only the members of a State, but the entire Human Species; and, by this title, ourselves, who have always battled absolute socialism, we are today designated as socialist. We are undoubtedly socialist, but in this sense: we are socialist, if you mean by socialism the Doctrine which will sacrifice none of the terms of the formula: Liberty, Fraternity, Equality, Unity, but which reconciles them all. (1847.) — I can only repeat here, with regard to the use of the word Socialism in all of this extract, what I said previously (pages 121 and 160 of this Volume). When I invented the term Socialism in order to oppose it to the term Individualism, I did not expect that, ten years later, that term would be used to express, in a general fashion, religious Democracy. What I attacked under that name, were the false systems advanced by the alleged disciples of Saint-Simon and by the alleged disciples of Rousseau led astray following Robespierre and Babœuf, without speaking of those who amalgamated at once Saint-Simon and Robespierre with de Maistre and Bonald. I refer the reader to the Histoire du Socialisme (which they will find in one of the following volumes of this edition), contenting myself to protest against those who have taken occasion from this to find me in contradiction with myself. (1850.)

“Course in Political Economy Presented at the Athénée of Marseille by M. Jules Leroux”

[section excluded from subsequent publications]

We will say no more about this fundamental point of political science; that would divert us from our goal. It is enough that we have indicated the metaphysical demonstration of the principle that we would like to posit.

Now, what is the consequence of what we have just said about political economy?

It is that every theory of political economy of which the tendency or conclusion would be either the present individualism, which crushes and denies the individuality of the masses for the profit of a few, or a blind socialism, which, under the pretext of devotion, would crush and deny the individuality of each and all for the profit of who-knows-what pipe-dream of society, could not be true. The only political economy that could be true would be that which, revealing to us the true nature of economic phenomena, would demonstrate that it is in the nature of these phenomena to lend themselves more and more to the needs and the development of these individualities, in such a way as to realize the formula: “The perfection of society is the result of the liberty of each and all.”

Now this, I repeat, is precisely the character of the truly new science, the existence of which my brother has just noted in the lessons he gave at the Athenaeum of Marseille. In my turn, I will attempt to make the ideas of my brother known in this volume. They will be the subject of one or more articles. What I have just said today is the preamble and natural exordium of that exposition. I have seen the sort of fury that drives all of society toward the search for material goods. No more nobility, no more clergy; no other direction, no other attraction, no other influence than wealth. I have wanted to show how the good will emerge from the evil, how that universal passion is the token of a future progress; how, without backsliding, society advances in this way toward a better state; how, finally, that which today causes so many immoral acts, so many political crimes, and so much profound misery in all ranks of society, yet proceeds by a mysterious tendency toward a superior morality. I have been led in this way to lift myself toward the very principle of politics, seeking the goal that society pursues, shaped at once by the two powerful instincts of individuality and association.

The recognition of these two needs, and the presentiment that they must be reconciled and harmonized in the transformed society that is to come, is truly the only light that can enlighten us regarding the value of an economic theory. It is with this touchstone that we can test and judge the ideas of that order. Indeed, why and how are we to concern ourselves with political economy if we do not see the link between political economy and politics itself? I repeat, if politics tends to individualism, Smith and Malthus are right: if it tends to socialism, we must wait for a theocrat to give us its law and persuade us of it; there is no more political economy to be done, everything concerning that science obviously being only an appendage, a deduction, a detail of the theocratic law to come. But, on the contrary, if it is proven that politics must tend, through association, to give each citizen their liberty and personality, we will ask political economy to tell us by what means the phenomena that are the object of its study will come to transform themselves in such a way that each citizen finds in association the instruments of the liberty and personality. That is to say that we will be lead to suspect the existence of a new science; for obviously neither the theory of Smith, nor the sketches of industrial organization of the theocrats, satisfy the conditions of the problem. Thus, from the ideal that we make of politics is derived an insight by which to judge the true character of an economic science. And even just the sentiment that we conceive about present reality, about society considered in relation to its tendency for material goods, is a guide and a light to enlighten us on the true character of an economic science. Indeed, if the search for material goods, understood as we understand it today, is absolutely good and legitimate, Smith et Malthus are right; if that greed for wealth absolutely merits the anathema, and if it must be replaced by pure devotion, the theocrats of every sort can give free rein to their imaginations. But if that hideous plague on our era is revealed to be good and legitimate in a relative manner, insofar as it leads to the aim of society, we have to draw from it an entirely different induction. Based on the actual lives of our contemporaries, we can say to the theory of Adam Smith that it is misleading, since it does not lead to a true goal, and we can also reject all the plans of organization birthed willy-nilly by a blind socialism; then, freed from the false, we can seek the true.

In any event, then, whether we consult the actual live of society and study the present in order to understand its tendencies, or whether we take the ideal of political perfection for our guide, we arrive at this conclusion: The only political economy that could be true would be that which, revealing to us the true nature of economic phenomena, would demonstrate that it is in the nature of these phenomena to lend themselves more and more to the needs and the development of these individualities, in such a way as to realize the formula: “The perfection of society is the result of the liberty of each and all.”

Now does this theory exist?

In the name of actual reality, source of certainty, and in the name of the ideal that we are forming of politics, we would respond that even if this theory does not yet exist, the science would be no less existent: though veiled, though still not revealed, it would exist none the less in the nature of things.

But we can say more; we can affirm that the first steps, at least, have been made down that road. That is what we will attempt to demonstrate clearly in the next in article.

In the meantime, we will detach today a fragment from the course given at the Athenaeum of Marseille, consisting of the two lessons on the question of wages.

Pierre Leroux.

“On the Search for Material Goods or Individualism and Socialism”

[Second section of first article, not reprinted in either Malthus and the Economists or the Oeuvres.]

§II.

When the preceding pages appeared, twelve years ago, one of the greatest minds of our time, then very attached to the system of Fourier, and very close to this thinker, whom death had not yet taken away, addressed us following letter:

Versailles, September 16, 1834.

“My dear L.

“I read with great pleasure your article Political Economy in the latest issue of the Revue. You finally arrive on practical ground, and from the moment you enter you firmly establish yourself there. Very often, I have regretted not being able to agree with you on some of these great principles, which carry with them all the details of a doctrine. But what you say today suits me perfectly; and as what you say is fundamental, I hope to be able to follow you with the same consent in the further development of your ideas, in the exposition of this new science, of this complete theory that you promise us. However, I cannot prevent myself from pointing out to you, at this moment, that the principles that you have just established are identical with those which the partisans of the domestic-agricultural association, with those that the followers of the societary theory have endeavored to establish on their side, if not with great success, at least with a firm conviction, which the current coincidence of your views with theirs can only strengthen. Perhaps you attach little importance to finding yourself, at some point, in connection of principles with Fourier; but the partisans of Fourier, and me especially, do not feel the same. Besides, would it not be too strange if this inventor had found nothing feasible, since he adopted principles a long time ago that are finally beginning to emerge today from all sides. On the other hand, I believe you are too just to refuse to recognize, if necessary, the right of first occupant to this man so little known, and so shamefully handed over to the feuilletonistes. Allow me therefore to review the truly progressive ideas that you have just put forward, and to compare them successively with our own, to show you the analogy.

“First idea: “Whether we appeal to religious traditions and the previous life of Humanity, or whether we only consult modern reason and the general consent of men in our time, far from condemning the use of material goods, we must see that none of our most generous faculties can be exercised without the intermediary of these goods.”

“From this, and from what you say about the main character of material renovation that the definitive social transformation must have, it follows that you must impose on the true doctrine a first condition, namely to create new material resources, new wealth to meet the needs of the multitude. Thus, you will no longer limit yourself to asking, like Saint-Simon, for moral, intellectual, and physical improvement. You now know, more than he does, that we must begin with physical improvement; that this is the first and essential guarantee to demand from every innovator; that without this, without the solution of the great industrial problems, any philosophical lucubration on the further destinies of Humanity is absolutely inappropriate, if not useless.

“And, for example, if we accept universal association as a definitive goal, and if we have the formula for it, we must be essentially concerned with the application of this formula to the particular fact of domestic-agricultural association. Because, on the one hand, how would we have a general formula if we did not provide this particular solution? And, on the other hand, how would our formula be feasible if it did not provide men with the means to exercise their most generous faculties, means that depend, according to you, on material goods, and which can come, therefore, only from the organization of factory, cultivation and household labor.

“We are therefore in complete agreement with you on this first point. But here is what you have feared. You feared that we would be completely absorbed in these cares of housekeeping, culture, and manufacturing. The stew, the vegetables, the shuttle, that’s all you will have seen in us. You thought that we circumscribed all social foresight in the supply of kitchens, and that we placed all the realities of the world in the narrow enclosure of a phalanstery, all the general and infinite science in the science which teaches how to form a household, a domestic-agricultural association!

“But this is a gross mistake, which we have noted a thousand times. In the establishment of the corporate household, we have always seen the beginning of the work, and not the whole work.

“To this beginning we attach immense practical value, because it is the beginning; but we know very well, and we have said it many times, that, after the establishment of this first term, it will be necessary to rise successively to the terms of a higher order: from the societary household, to the societary canton; from the canton, to the province; from the province, to the empire, and finally to the spherical unity.

“In truth, we also attach great philosophical importance to this beginning, and this may have contributed to the change; but this, on the contrary, was to prove to every unprejudiced mind that we did not at all want to abdicate the higher views of religion and philosophy. For we considered the application of a general formula to the creation of a very limited association, but finally forming a complete whole and an integral mechanism, we considered this application as sufficient to justify the formula itself in its generality; and we never stopped saying: Deign, gentlemen, to submit to examination, to discussion, to experimentation, the theory of the phalanstery; because if the great problem of using all classes, all ages, all sexes, all characters harmoniously has been resolved, it is a clear sign that M. Fourier possesses the key to true social destinies.

“In this we were of the same feeling as Wronsky, when he said: ‘It is necessary to recognize the necessity of a uniform law for the creation of all reality, because, without such a law, no unity would be conceivable, in the various realities that make up the universe; or rather, without a creative law, reality itself cannot exist. As such, this law, which presides over the generation of all realities, and which thus manifestly forms the law of creation, is precisely that which determines the very essence of all that exists in the universe; and consequently it is on the discovery of this august law, the idea of which man has until now been unable to conceive, that the peremptory establishment of human knowledge depends.’ (Messianisme, 1831) Therefore, as it is well proven today that it is up to Humanity itself to create the social organization, all the materials of which have been given to it in its own nature and in external nature, we asked publicity and experimentation to examine and test whether Fourier, by applying to human labor the organization by groups and series, which is the universal mode of distribution of all beings in the universe, had not truly indicated this august law of all reality, from which it would then be easy to deduce the organization, not of a simple commune, but of the whole of Humanity, and from which we could finally conclude the general destinies of the species as well. This is how Fourier himself always understood it, and, from his prospectus (1808), he expressed, in other words, but with no less clarity and energy, the lofty thoughts of Wronsky.

“It therefore seems to me, my dear L., that we are in agreement on this first idea that I extracted from your article; and it is no less well known that this idea has for us the only significance and the only value that it should have; that is to say, we have never claimed to limit social science to the edification of the household, nor to in any way erase moral and intellectual improvement from our motto; which would be extremely shameful. But, to tell the truth, I do not believe that such a fault can be attributed to any thinker, not even to those whom you pursue by the name of Doctrinaires. And now I continue.

“Second idea: “It is his dignity, his quality as a man, it is his liberty, it is his independence, that the proletarian claims, when he aspires to possess material goods. It is the same feeling that pushes those who own these goods to keep them… In the current struggle of the proletarians against the bourgeoisie, that is to say of those who do not possess the instruments of labor against those who do, the bourgeoisie even represents, at first glance, more obviously than the proletarians, the feeling of individuality and liberty. The rich have this freedom and they defend it. We find good and legitimate this tendency of those who possess liberty and individuality to preserve them, etc.”

“As the first idea was the essential starting point of every absolute doctrine, this is the no less valuable starting point of every transitional doctrine; this is the true appreciation of current events; it is the true basis of all practical policy consistent with reason.

“By this you definitively break with the tradition of Saint-Simonism, whose fallacious maneuver wanted very gently, without violence and by benign persuasion, to get the rich to lay down all their privileges, of their own free will and by voluntary consent.

“And, at the same time, you separate yourself no less decisively from vulgar republicanism. Because, by virtue of these principles, you will undoubtedly show the radical falsity of the connection that we wanted to make between the two great moments of the social transformation caused by France. The first moment was the struggle of the bourgeoisie, which mobilized the people against the privileges of the nobility and the clergy. The second moment, as they would like to make it to us, would be the struggle of the proletariat against the privileges of the bourgeoisie, the struggle of those who do not possess against those who possess.

“But you will restore the truth in its light, and you will say: No, there is no identity there, no equality of positions. The privileges of the nobility and the clergy were unjust and undeserved, their tendency bad and illegitimate, their superiority illusory at bottom; because in the end, what bourgeois of 89 would have thought he would elevate himself by becoming a monk or a marquis! But the current privileges of the bourgeoisie, that is to say its wealth, its goods, the ownership of material goods, ah! these are just and well-deserved privileges; the tendency they have to keep them is good in itself and legitimate: it is for them the price of previous labor, and, without wanting to lower them to our infirmity, we other proletarians know how to find the means to elevate ourselves to their superiority.

“In a word, it will no longer be a question, by violence or by sympathy, by Babouvism or by Enfantinism, of taking anything away from the upper class; and yet it will be necessary to give to the lower classes.

“Give to the classes that do not possess, without taking anything away from those that possess; this is the great and delicate commitment you have come to make. And this is the great difficulty of the latest crisis! Hic opus, hic labor est!

“But what! Isn’t this also the difficulty that societary theory has posed? And, if I dare to speak thus, do you not still remain behind us in this way? For not only do we guarantee the rich the preservation of their wealth, but, to interest them directly in the improvement of the people, we increase in a high proportion all their pleasures, all their enjoyments; to put it all in a nutshell, we bring an increase in wealth to the richest.

“Thus, this very essential point of practical politics, this legitimization of the tendencies of the bourgeoisie, this doctrine that implicitly condemns any violent revolution, any riot, and even any peaceful attempt at renovation, if such renovation does not above all consolidate the natural and legitimate privileges of the bourgeoisie; this doctrine that will clearly outline you among the parties, and which already separates you from yourself, that is to say from the means previously proposed by you in the Revue, as I would establish without difficulty if I had time; this doctrine is still quite common to you and us. Let us see if this happy coincidence will be maintained in what follows.

“Third idea. “Pure devotion, however noble it may be, is only a particular passion, or, if you like, a particular virtue of human nature; but it is not the whole of human nature. A man who, throughout his life, would be placed in the point of view of devotion, would be an insane person, and a society of men whose sole rule would be devotion, and who would regard every individual act as bad, would be an absurd society. Any theory, therefore, that would like to be based on devotion as on the most general formula of society, and which would then deduce from this formula the laws and institutions that it would hope to apply by force to society, would be false and dangerous. But, on the contrary, a general principle that represents and formulates complete nature is the principle of liberty and individuality, etc.

“That’s what they say; — Well! Am I saying something else!

“Have we ever denied the sublime faculty that man has of sacrificing inferior inclinations to noble passions? Do we not know that to him alone, in all creation, it was permitted to give his fortune and his life in testimony to the eternal principles of justice and truth! And without raising ourselves so high, in the minimal detail of the societary organization, could M. Fourier have misunderstood, he who claims to use all the passions, the useful passion of devotion? In the pivotal problem of the passionate agreement in the distribution of benefits, does he not employ greed and generosity concurrently, and as a reciprocal counterbalance? Did he not institute as an essential cog in his mechanism corporations dedicated by essence to the service of the public good, such as the small and large hordes, the vestalate, etc.? We not only honor devotion, but we employ this sublime portion of human nature in due measure. On the other hand, we start from this principle that social harmony must not borrow anything from constraint or sacrifice; that it must rest essentially on the free development of passions, characters and instincts; and, to give the measure of our liberal theory in this respect, we claim to use even the discords, repugnances and natural antipathies, which until now all doctrine has considered as errors of creation, products of evil, anomalies! Yet you know well, from Geoffroy, that there are no anomalies in the great works of nature. But then you believed that we accepted all the vices of a society monstrously deviated from its destinies; and, seeing in all the corruptions that are among the civilized the incontestable effects of passions, you distanced yourself from us, thinking that we were going to deify these vices and these corruptions. M. Fourier answers you with a single phrase as profound as it is decisive: these are the effects of passion in subversive growth. But it is in his books that we must see the proof.

“Now does the societary theory indeed provide the development of individuality? Does it ensure complete and true liberty for all? This is what must be examined separately. But finally, if the science that you announce to us keeps, on the fact of liberty and individuality, the promises that you make, what other course should this science follow than the methodical course adopted by us: first to study the instincts, tastes, passions of individuals, of different ages and of different sexes; and, when it has completely carried out this analysis, to present a mode of organization that promises, that ensures a free development for these passions, these tastes, these instincts.

“Because you do not want these words, liberty and individuality, to be empty of meaning, as they have been until now for all revolutionary schools, you do not limit yourself to these negative liberties, such as freedom of the press, freedom of education, of religion, etc., which are the common basis of all critical doctrines, and which are likewise the basis of the thought of Mr. Lamennais, as you could see in his article in the Revue des Deux-Mondes (Dialoghetti), an inconceivable poverty in a man nourished entirely by organic doctrines! But such is the precious justice of our time: Mr. Lamennais is exalted to the skies for having, after forty years, reproduced in a new form what has already been said, and above all established at the cost of so much blood; but if some obscure shop sergeant brings great and real novelties, we persist in ignoring him. What does this priest bring us, however eloquent he may be, that we children of the Revolution certainly did not know before him, and perhaps as well as him? Ah! Let us prostrate ourselves before the high genius of De Maistre. He opened our eyes; he reduced us to confessing that all truth was not included in the truths proclaimed by the French Revolution; he showed us on how many points this eighteenth century philosophy with which we were nourished was frivolous, superficial, and blindly unjust. But when we find under the poetic effervescence of Mr. Lamennais only the pure principles of the Revolution, what can we see in his unexpected escape but a new sign of the times, a new proof of the irrefragable antinomy of the two doctrines that share the world, and which, although today exclusive of one another, nevertheless each contain their share of truth!

“Saint-Simonism had begun this proof, and M. Lamennais came to complete it. M. Lamennais forms the counterpart of Saint-Simonism; Nothing more, nothing less.

“Saint-Simonism, coming from the most radical liberalism, one day fell in love with admiring the principles of order, unity, religion! And from admiration to admiration, it allowed itself to fall into the doctrines of the most complete despotism.

“Representative among us of Catholicism, Mr. Lamennais recognized what is true, absolute, eternally imperishable in the ideas of equality and liberty; and then, ignoring the fatal antimony that, at the current moment of the development of the human spirit, separates these same ideas from the principles of order and unity that he, a Catholic priest, had the mission to incessantly remind us of, Mr. Lamennais been precipitated into the dissolving doctrines of negative freedom (see the Dialoghetti).

“But because Mr. Lamennais stutters the misunderstood words of progress and association, he is an oracle; a genius! a poet! a prophet! an apostle! and a resounding voice was heard at the back of the sanctuary crying: He is saved!!! (Revue des Deux Mondes, August 1). O literati! literati! Will you spoil our social work, as your cousins the lawyers spoiled our political work? Litterateurs, will you never have eyes and ears, and sentences so agreeable, as in favor of the men who are in your path? For there is a man who believes in liberty and individuality, and who, on these great principles, founded a vast doctrine, but who also believes in society, in association, and who pointed out the natural law, the universal principle, the application of which will make it possible to bring together, to associate, to socialize without despotism, without constraint, without sacrifice, all liberties, all individualities. And this man’s labors are worthless to you! You do not want to take this work, which would put the French school, immediately and without question, at the head of all the others. You prefer to applaud the inconsistencies of Lamennais and Chateaubriand. Certainly we had to iron them out when they brought back into honor the genius of a stupidly misunderstood religion, or when they awakened with thunderbolts of logic and eloquence our shameful indifference in matters of religion. But today when they come to pay homage to the truths that they had ignored on their part, let us let these illustrious geniuses complete their education, and look for teachers less prone to error. So help us to bring to light in the eyes of the people the name of a man who emerged from the people, of a man who for twenty-five years has not yet been challenged on any great idea of the past or the future; of a man who, without changing at all, never had but one thought, one goal, one faith: free association; association by and for liberty, association of all classes; the association that will call the rich back to work by creating attractive industry, and which, through this true and natural industry, will save the workers from the brutalization to which odious industrialism reduces them!

“All this, my dear L., is not a digression; because I have taken the opportunity to touch on the fourth idea which is prominent in your article which is so important and so decisive

“Fourth idea: “Liberty and Society are the two equal poles of social science. Do not say that society is only the result, the whole, the aggregation of individuals, but do not say either that society is everything, and that the individual is nothing, or that society is before individuals, or that citizens are nothing other than devoted subjects of society, functionaries of society, who must find goodwill despite their satisfaction in everything that contributes to the social goal, etc. Today we are prey to these two exclusive systems. Our perplexity will only cease when social science has succeeded in harmonizing these two principles, etc.”

“You have here grasped and pointed out the fact that truly characterizes our era from a philosophical point of view. It is, as you say, Humanity suspended between two contrary attractions; on both sides, there is truth, although, through a fatal mystery that it is reserved for social science to clarify, each side is the negation of the other. Such is the great and terrible antinomy that caused the double fall of Saint-Simonism and M. Lamennais, and which was so admirably revealed by Wronsky; an antinomy that separates the doctrine of experience from that of feeling, the liberal party from the illiberal party.

“I look forward to seeing you grapple with these great difficulties. But it is already rendering a great service to point them out with so much accuracy, and to divide so clearly all the doctrines that have been produced until now into only two distinct classes; because between what you call socialism and individualism, what can interpose (except the discovery promised to social science), only vain and illogical doctrines, powerless to satisfy us.

“In the meantime, I place on your conscience this simple question: Does the societary theory rank among the doctrines of socialism, or among those of individualism? Are we reducing government to policing functions? Are we introducing an atheist law? Do we place each of us on our own mound of earth, independent, and absolute sovereign, with the stupefying motto of Everyone at home, everyone for themselves? Or, on the other hand, have we absorbed all individuality into the bosom of a tyrannical government? Have we made each citizen a humble and submissive subject, without any spontaneity? Is he a regimented official, having an official doctrine to believe, and the inquisition at his door? Ah! Answer, my dear L., these serious questions. Let us know, finally, if it is only for lack of knowing it that you always pass over our doctrine in silence, or if you have any opinion on it based in right and reason.

“Or would you deny M. Fourier a true doctrine, a doctrine worthy of the name? If this were the case, which I cannot believe, I would have only one thing left to say to you: ‘You summarize your entire article in this broad and fundamental proposition: “The only political economy which can be true” would be the one that, revealing to us the true nature of economic phenomena, would demonstrate that it is the nature of these phenomena to lend themselves more and more to the needs and development of individualities, so as to achieve the formula: The perfection of society is the result of the liberty of each and every person.’

“Well! If you want to take with me a hundred or so pages of Fourier’s writings, I will undertake to show you the revealed nature of economic phenomena, as well as the irrefutable deduction of the following two facts:

“1. That in the incoherence and fragmentation (individualism) that characterize the current phase of civilization, as well as in the false association with which industrialism threatens us, into which the fatal example of England leads us, in the false association that would become the eminent character of the later phase, the economic phenomena (production, distribution, and consumption) are absolutely and necessarily incompatible with the development of individual faculties as much among the rich, or at least almost as much, as among the poor;

“2. That in societies with a shareholder base, in which labor will be organized according to the law of natural and universal distribution, the same economic phenomena become, on the contrary, the assured means of developing all individualities, and of bringing about social improvement from the liberty of each and every person.

“Thus, my dear L., I have shown that the societary theory is in conformity with you with regard to the main ideas that you put forward in your article, and that, finally, I have accepted as the criterion of our doctrine, for us, the basis that you take for yours. After all this, I do not intend to prejudge anything about the novelty of the ideas you promise to produce. When you have explained them, I will tell you my way of thinking, if you do not fear wasting time following all my lengths. Today I only wanted to note the conformity of our principles; and as this conformity gives me the strong desire to see the consequence on your part, I like to think that it will lead you, for your part, to consider, finally, in a serious manner the immense works of Fourier. This is my whole goal, convinced that societary ideas would benefit infinitely from being adopted and defended, or even simply discussed (but with full knowledge of the facts), by you and all those of conscience and talent who are with you. On that note, excuse this jumble, and receive my best regards.”

———